On Agency

essays ·Tl;dr: lots of people benefit from pursuing “agency”. But there are nearby concepts that are bad for you. Agents don’t have to become impressive rule-breaking boss types if that doesn’t actually achieve their goals. Individual agency can undermine groups. Agency can backfire if you lack knowledge and incorrectly reject commonsense. Learning your goals will take a lifetime and you can reward hack yourself by mistake. Sometimes you need to listen to your heart even when your goal-directed reasoning would take you somewhere else.

Some communities are big on “agency”. It typically means something like: (a) have goals and (b) do things to achieve those goals. There’s a secret and important third thing like: (c) have your goals be your actual goals and not something more normal or easy-to-achieve that you can persuade yourself is your goal instead.

Agency is, indeed, an important trait/skill.

The motto I like for it is: “do things for reasons”. Though that doesn’t fully capture it.

But I think there are some bugs in the ways that some communities end up actualizing agency. I am particularly thinking of entrepreneurship, rationalism, and effective altruism. Points that I think are undervalued are:

- Agency is about goal-seeking and not impact-owning or being the boss.

- Individual-level goals and group flourishing can be in tension.

- Agency plus ignorance can be accidentally destructive.

- Goal-understanding is a long and hard process.

- Sometimes your spirit has to sing.

First, a common pattern for people who recognize the importance of having more agency is to seek a big impressive impactful goal that they can be in charge of and lead. They have learned that agentic people are in charge and follow their own rules.

This is half the truth, but is missing something important. People who self-identify as agentic are more likely to seek a big impactful goal than the average person, partly because a person who has relatively normal individual-level goals usually doesn’t need to find the word “agentic” as a label for themselves. But it is entirely possible that your goals do not include anything impressive or impactful. By all means go for it if they do, but don’t feel that you are bad or wrong if you actually do have goals that are more limited in scope. Agentic people don’t blindly follow rules without a reason, and will follow fewer rules than the average person. But some rules are good! And some rules are useful to follow even when they are bad rules. Agentic people will be more likely to be leaders, because it is often the case that achieving a goal requires leadership. But not always! Sometimes there is already a good leader who has sufficiently similar goals to you and you are far better off helping them lead effectively.

Ironically, I think that many people who want to be agentic are role-playing a stereotype of an agentic person without really reflecting on whether someone who acts like that stereotype actually achieves their goals.

Second, many framings of agency are unhelpfully self-focused. They invite you to do whatever it takes to pursue your goals, and to set aside social norms that might block you. Many of those norms are implicitly protecting people from each other. And many forms of “agency” actively encourage behaviour that comes at the expense of the less “agentic”. One gloss: these framings invite you to be more Slytherin and less Hufflepuff. Whether or not this is wise for the individual, it is bad for groups. A group of people who are comfortable defecting if it helps them pursue their individual goals will find it very hard to achieve certain kinds of coordination that less “agentic” people will find almost automatic. Groups that lionise agency can therefore suffer if they underemphasise the importance of virtuous and considerate agency. Individuals who care about their group’s flourishing should care about this, even if only selfishly. Note that it is entirely possible to become someone who is better at doing-things-for-reasons without becoming manipulative/scheming/exploitative, and indeed becoming a more virtuous and kinder person might be one of your goals.

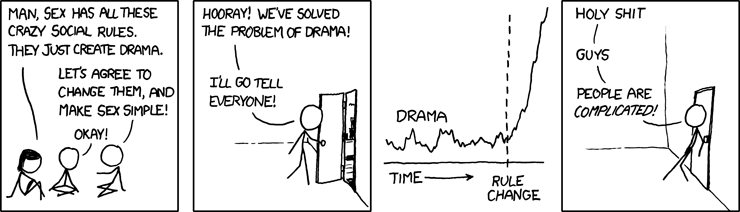

Third, agency pairs particularly poorly with ignorance, especially insofar as agency often goes alongside rejecting commonsense norms and behaviours. We all know about Chesterton’s fence in the context of political reform, but it’s really important in the context of personal relationships. Social dynamics are complicated. You may be really really good at understanding them, but you are probably missing something. You should be careful and methodical about doing things very differently from how most people do them, and recognise that they might be done for important reasons that you don’t understand yet.

Even outside how we treat other people, agency can be a mixed blessing. Acting in pursuit of your goals when you understand how to pursue them can be great. But sometimes you are wrong about how to pursue them, and you may have no idea that you are. Often, being normal protects us from the consequences of our unusual beliefs in case we turn out to be wrong.

Fourth, many people who pursue agency underestimate how hard it is to understand and nurture your own goals. There is a boilerplate that I write fairly often in one way or another: “When the reward is perfectly specified, reinforcement learning can work well. But when the reward is misspecified or partially specified the agent will often learn reward hacking behaviours: where it achieves a high reward without doing what its designers intended.”

It is easy to accidentally do this to yourself. Being explicitly agentic usually involves (a) consciously identifying goals (b) consciously picking some action over another because it seems to better achieve that goal (c) based on this reasoning, overriding something else in your character that would have picked an alternative.

If you are right about your goals, and you are right about your reasoning, then this might be a great choice. But, even if your reasoning is right, if you are wrong about what your goals are, you might be reward hacking yourself.

Certainly, when you notice that you are picking something that you intuitively disprefer in order to achieve a goal, you are also noticing evidence about what your true goals might be. It is noisy and unreliable evidence, but don’t ignore it. I have known people who were in denial about their goals who gradually become less and less enthusiastic about everything they do. They wish they had different goals than they do, but refuse to notice or accept this. This only works for a short while.

It is possible to change your goals, to persuade yourself to value something you didn’t value before. This sounds odd, but this is basically what it means to mature as a person. But don’t expect it to happen by sheer force of will.

Certain kinds of education, especially ones that are focused more on studying and engaging with literature or having really thoughtful discussions about character and virtue, seem to me to be more helpful at supporting this than educations that center on business or technical skills. This is a shame, because a truly skillful agent must learn their goals as well as learning to achieve them. (Of course, I don’t think this kind of education is either necessary or sufficient. And often people seem to be able to use literature or philosophy to contort their psyches into the most unnatural uncomfortable shapes.)

Fifth, I think there is something to be said for letting your spirit sing and acting from joy. One thing I advise the PhD students I have worked with is to learn to love discovery and curiosity, to learn to savour surprises. The main reason is that I think almost nothing else works. If you want to be able to pursue research for long periods of time despite setbacks you do ultimately have to be having fun doing it. It sort of doesn’t matter if you see becoming a researcher as the best way for you to achieve some goal if it is going to be a struggle against your character and spirit every day.

You are not injection-moldable plastic. You are wood and you grew. Work with your grain, not against it.

I think the effective altruist world made a relatively subtle mistake in the early days of 80,000 Hours in positioning its career advice in opposition to the idea of “following your passion”. There was wisdom in the observation that you can grow a passion, that you can shape a passion, and that being passionate in service of some goals can be much more impactful than others. Passion isn’t enough. But passion is also an important ingredient and you cannot always create it.

Thanks especially to Toby Ord for conversations about this topic and especially the ideas in the second item. Thanks also to Becky Cotton-Barratt, Owen Cotton-Barratt, and Neel Nanda for comments on a draft of this post.

PS: I think this is a quite good post by Neel Nanda on some aspects of developing a healthy kind of agency.